Komodo Island

Komodo Dragons

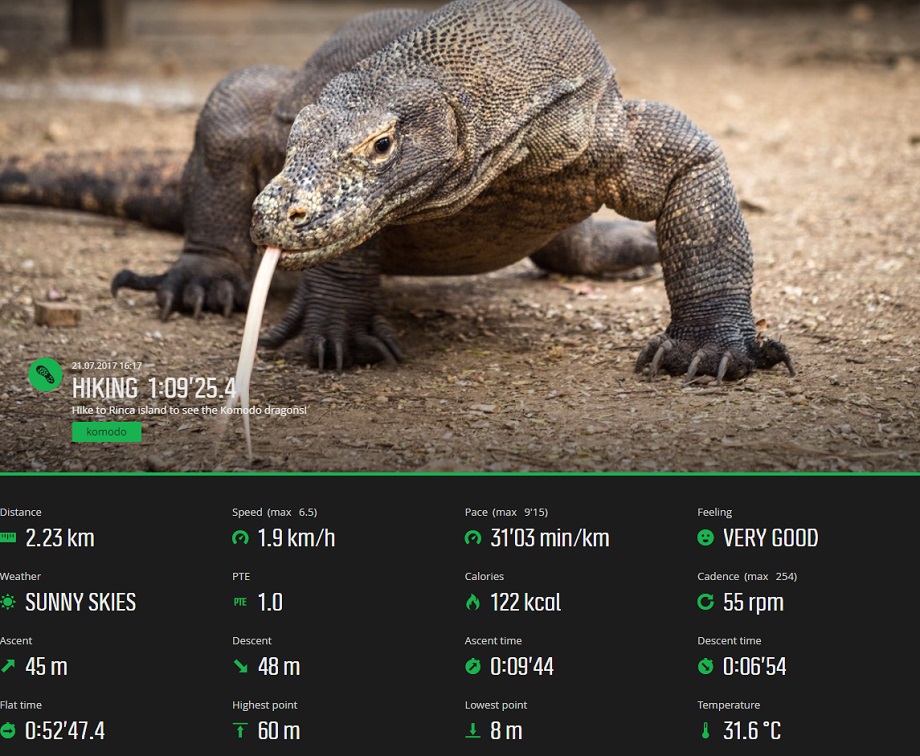

The myths and legends that were inspired by the Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis) are quite fantastic, and when you see your first dragon, it will be fairly easy to see why they are. The dragons are massive, and can reach up to 3 metres in length and can weigh up to 70kg. They appear slow as they lumber around in the midday sun, their tongues flicking in and out tasting the air (they can 'taste' dead meat from up to eight kilometres away) as they carry their huge heft, but they can be frightfully fast when ambushing prey and are able to make short bursts of almost 20 km/h. They don't take down their prey immediately though, and instead land a bite that is filled with venom.

It wasn't until 2009 that a researcher called Bryan Fry found that the venom rapidly decreases blood pressure as well as expedites blood loss. This in turn leads to a huge reduction in blood perfusion (shock), rendering the prey too weak to escape or to fight. This explains how the Komodo dragon can prey on much larger animals such as the Timor deer (Rusa timorensis) and the water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis).

Komodo Dragons only have a population of approximately 4000 individuals, which means that the species is listed as 'vulnerable'. They can only be seen at two locations in Komodo National Park: Loh Liang on Komodo Island or Loh Buaya on Rinca Island. Local rangers stand watchful and vigilant at these locations and are armed with long forked sticks in order to keep the daring dragons at bay. The rangers will accompany you as you hike along trails of different lengths, and will not only point out the dragons that they spot, but also the huge pits that they dig when the females nest. Interestingly, it has been found that the females can also reproduce asexually through a process called parthenogenesis, whereby they still lay eggs even when no males are present.

Draco

Another dragon can be seen here every night when the skies are clear of clouds. Each and every time we emerged from the water after a night dive, we were stunned by the magnificent milky way that blazed overhead. Scorpio was undoubtedly there too, its tail curled up towards Saturn, and Jupiter was fairly obvious off to the west. When looking over to the north however, the constellation of Draco could be seen cheekily peaking above the horizon.

Despite not being very bright, Draco is fairly easy to find. All one needs to do is to trace a line from the two pointer stars, α & β UMa, (the northern version of α & β Cen for the southern cross) on the rim of Ursa Major (the Big Dipper) towards Polaris (α UMi) at the end of Ursa Minor. The first star that the line encounters (albeit a little to the left) is the start of the tail of the dragon. Draco curls around, and practically wraps around, the front of Ursa Minor before swinging its head back out, almost as if it were trying to avoid the Cat’s Eye Nebula (NGC 6543), maybe as a mark of respect since it was the first ever planetary nebula to be discovered.

One interesting thing to note about the constellation of Draco is that one of its stars, Thuban (α Dra), used to be the north pole star from the 4th to the 2nd millennium BCE. This is due to the slight and very slow 'wobble' of earth's axis (called precession), that takes 26000 years for one cycle to complete.

We might not be around when another cycle completes but the enduring legends of fire-breathing dragons could easily still be!

Route Playback